I (virtually) sat down with Avraham Cornfeld of AlefAlefAlef and Fontimonim to talk about his work in reviving Hebrew type, and why it’s so valuable today.

In the classic sense, a revival typeface is based on an existing, often older typeface. In a looser sense, it could even extend to fonts inspired by older lettering. Either way, the choice of how literal or how loosely a font follows the original sits on a wide spectrum of typographic considerations. For Avraham, it is often a balance of honouring the type, fine-tuning it for today’s use, and bringing his own personal touch to it. “Some other designers might decide to keep the font exactly how it was,” Avraham explains, “but when I do a revival, I like to change it a little bit – even through small nuances, to make it more modern and usable.” This can be as subtle as tidying up proportions, or as intentional as creating additional glyphs, weights and scripts. “When I do a revival, I also want it to be mine,” he says. “This is how language develops – we build on top of each other’s work.”

Classic Revivals: FrankRe & Haim Classic

Font "FrankRe"

FrankRe is based on the classic font Frank-Rühl. Designed by Rafael Frank (1867-1920), Frank-Rühl is known as Hebrew’s first modern typeface and the most used in Hebrew print. Avraham’s work on FrankRe over the last ten years not only refines the typeface but expands its inclusivity as a bilingual font, even including an italic weight. This design choice, while outside the realms of a literal revival, was intent on making FrankRe even more relevant to users today. “Italics aren’t part of Hebrew letter culture,” Avraham points out, “but I wanted to imagine what FrankRe in italics could look like, especially as a bilingual font.” As English words are often used today within Hebrew writing, it was important for Avraham that FrankRe’s Hebrew and Latin counterparts talked to each other. Unusually for the Latin, its italics slant to the left to match the Hebrew. More subtly, many of the Hebrew details have been softened to compliment the Latin serifs when used side-by-side, achieving a more genuine typographic harmony. It’s a strong example of how purposefully addressing a revival with a contemporary approach can maintain its relevance and usability.

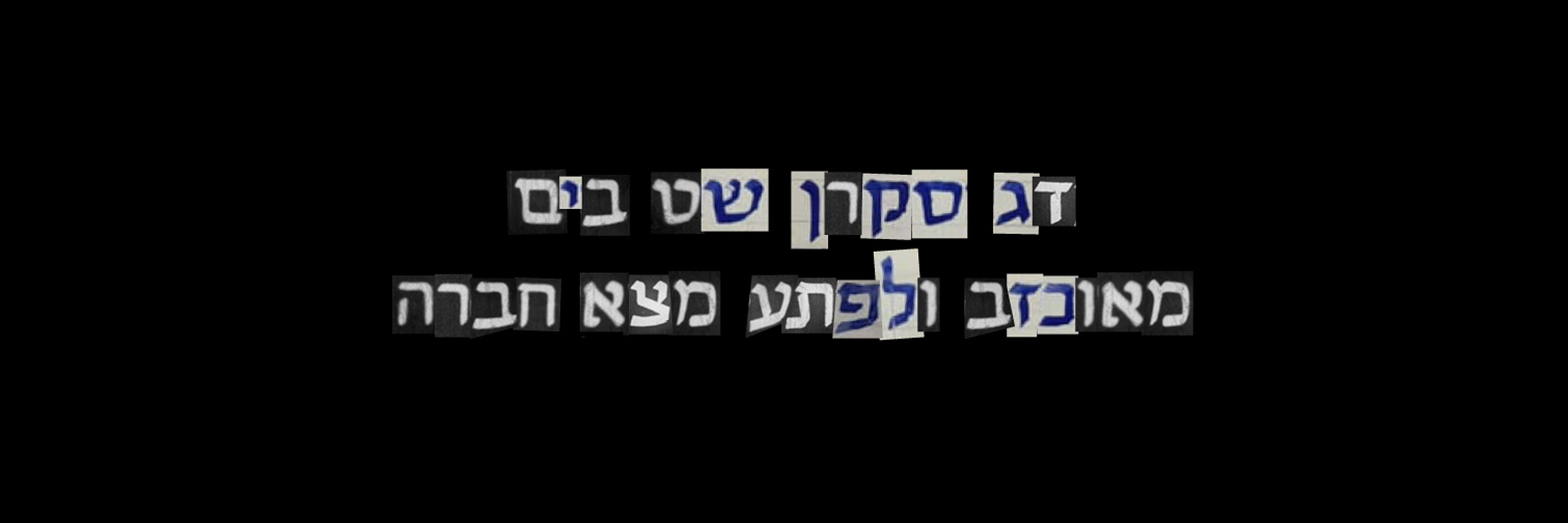

The also-classic typeface Haim has been widely used in print since the 1930s. Although it is a relatively simple font, it was harder to maintain typographically over the decades, compromising on its quality. Avraham shares the original Haim, pointing out a few inconsistencies of the widths (like the Mem and Bet) and angles (Like the Alef and Tsadik) across different letters, and why it needed a genuine revival. Comparing Haim to his typeface Haim Classic, it’s clearly since been balanced out more effectively while retaining its bold, geometric essence. “I didn’t change it too much, but the proportions make more sense now.” he explains.

Revival at Heart: Kedem & The Bau Family

"Hagana" Poster by Ismar David.

In contrast, referencing lettering rather than a complete font offers more room for interpretation in a revival. Avraham introduces the German-American graphic and type designer Ismar David (1910-1996), known best for designing the font David Hebrew. “He also designed posters in Hebrew,” Avraham adds – presenting David’s Hagana poster from the 1940s – “and I ran into [this], and thought that they were really beautiful letters.” With only six characters to reference, the font Kedem Serif was slowly born. Avraham’s earlier versions matched David’s poster lettering more closely, and over the design process it developed into the wide, multilingual typeface that Kedem Serif resembles today. This was followed later by Kedem Sans, initiated by a few client requests. “People prefer it without the serifs,” he notes. “It has a nostalgic 70s look.” The Kedem family in this sense carries a uniquely layered 20th century aesthetic.

On the note of heritage, reviving a font can also serve as a mission of preservation. After a visit to Tel-Aviv’s museum of Israeli artist Joseph Bau (1920-2002), a new project was launched between Avraham and the Bau family to preserve and celebrate the designer’s graphic legacy. This collaborative effort evolved into three fonts, all based variably on Joseph Bau’s type. The first of these, Rivka Bau, is a bilingual typeface in 2 weights inspired by the lettering on a sticker, with only 11 or 12 letterforms to reference. Tslilah Bau followed, a brush font which also includes glyphs based on older, less-recognised letterforms. The third and newly-released font of this series is Hadas Bau, a calligraphic serif in 3 weights. “The font was really re-designed” Avraham explains. “But since we worked on it with the family, we consider it a revival.” Although it’s been noticeably developed into a more usable serif, choices were made to retain aspects of the original, including the vintage, extra-tall Lamed as an alternative glyph.

Telling A Story

With fewer fonts, specimens and designers in Hebrew, reviving Hebrew type has some limits and challenges compared to Latin. “There are more people in the world working on Latin,” Avraham explains, “And there’s been more time and attention to the details. So overall, there are more fonts waiting to be revived in Hebrew than in Latin.” Having said that, he admits that with a limited range of Hebrew type specimens, there’s less out there to revive in the literal sense – but for this reason, revival type can also look to other visual inspiration. As long as it falls within public domain, there are many sources of lettering and design across Israeli and Jewish art to commemorate or develop. “Every revival has its own story,” he reflects. "You always have to know what the story of your font is: What added value you’re bringing to it, and why you’re doing it.”